Six months ago, my supervisor received an invitation to review a manuscript for a journal. However, due to his busy schedule, he delegated this task to me, with the final decision still under his control. This marked the beginning of my journey into the world of peer review.

When I review a paper, the first thing I look at is the language. Simple language errors can immediately lower my impression of the paper. Logical connections and cause-and-effect relationships are also crucial. Then, I examine the paper’s Abstract, Conclusion, and overall structure. I quickly skim through the figures and data to get a general impression before diving into the details. The Introduction is next on my list. As the papers I review are usually related to my research field, I can gauge the authors’ understanding of the topic from the Introduction. As a reviewer, I want to see references to classic papers as well as innovative research from recent years.

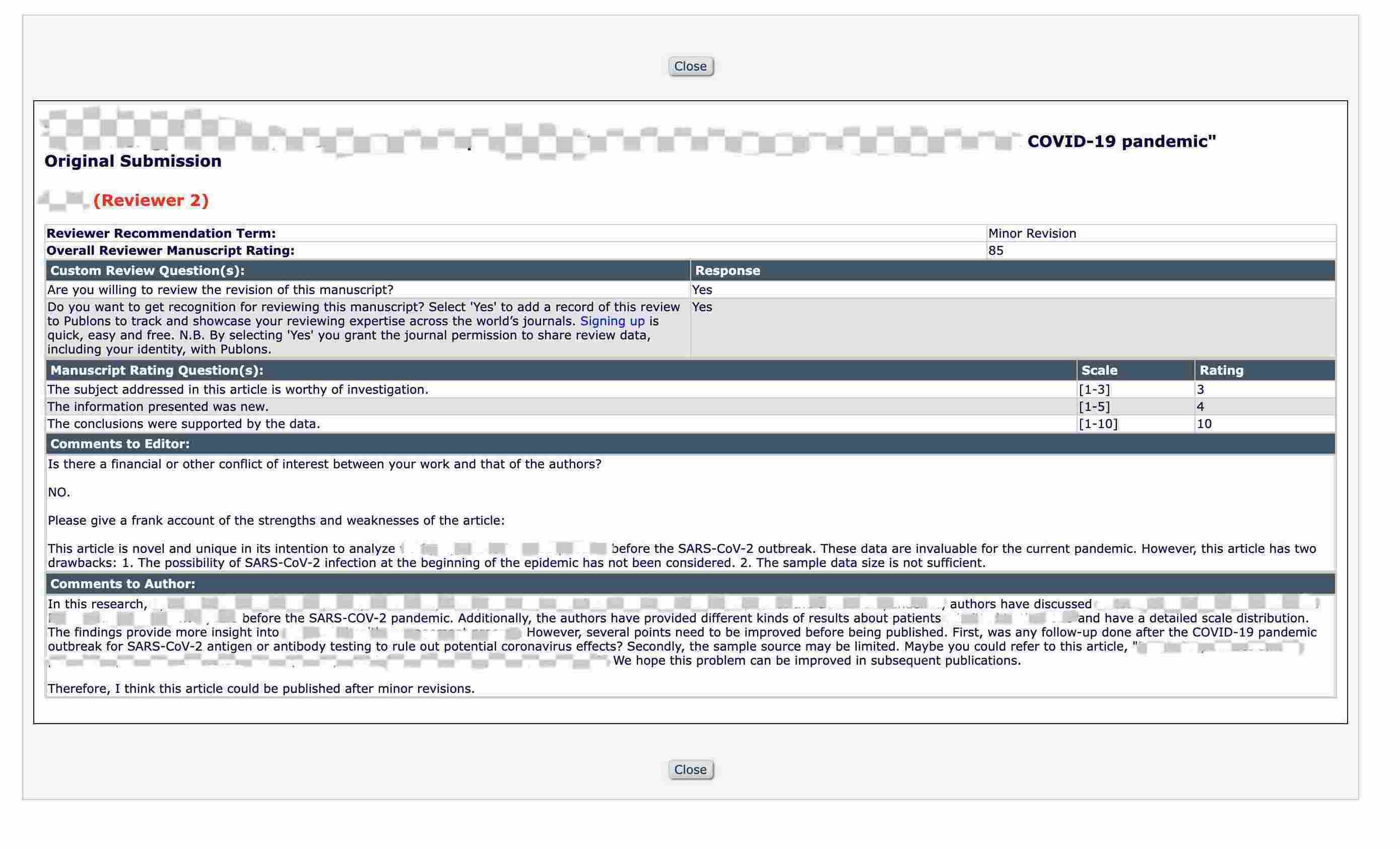

The motivation behind the research is another aspect I pay close attention to. The paper I mentioned above had a somewhat vague motivation. It touched on the hot topic of SARS-CoV-2, but unfortunately, its practical significance was lacking. The paper mentioned the epidemiology of a certain disease in the ICU before the COVID-19 pandemic, but it didn’t provide a detailed explanation or references to support the motivation for the experiment. As someone who has been through this process, I understand what might have happened. The authors might have had a sudden new idea, but the motivation for this new idea might lack precedent, so they completed it with a “let’s see what happens” attitude. As a result, the Introduction was vague about the motivation for the experiment. The experiment was not comprehensive, only describing the epidemiological trend before the pandemic. If data after the pandemic were added, the experiment would appear more complete, and the paper would be more convincing.

Next, I delve into the content of the paper. I don’t usually scrutinize the experimental methods line by line, but I can generally identify any flaws based on the authors’ descriptions. If key steps are skipped, I question the authenticity of the paper and ask the authors for additional explanations. Lastly, I consider reproducibility. From my overall understanding of scientific research, I prioritize the practical value of the research and whether it has the potential for future clinical application. If the research motivation is unclear, how can its superiority be articulated? We all have a certain level of subjectivity in scientific research, but the key is how to realize it better. Even if the research is basic, it can be described in a fascinating yet rigorous way within a reasonable scope. Not all researchers are Einsteins; for ordinary people, even a small breakthrough is very meaningful. Our job is to promote our achievements in the most rigorous scientific language within a reasonable range.

The above are the thoughts of a novice reviewer. I hope they can be of help to you.